PART 2: 1854–1866

In April 1857 a group of nineteen women assembled ten miles north of Salt Lake City and defined the work they proposed to do “under the name of the Female Relief Society of the City Bountiful.” Their charter read: “We … whose names shall hereafter be attached … ever feeling a lively duty in our Redeemer’s Kingdom, and for the general welfare of Zion’s cause, Do mutually unite ourselves together for the benefit of the poor and all other Charitable purposes wherein we can prove ourselves useful to our fellow creatures.”1 The statement, with its emphasis on charity and usefulness, suggests the purpose and variety of work undertaken by many of the first Latter-day Saint Relief Societies in the West. Largely isolated within local wards or congregations, most of the Relief Societies organized during this period functioned for four years or less, and sometimes discontinuously. Notwithstanding the earnest intentions of its members, the 1857 “Female Relief Society of the City Bountiful” operated for only six months.2 Early Utah Relief Societies lacked the centralized leadership, organizational procedures, and expanded responsibilities that strengthened and invigorated those permanently reestablished after 1867. Yet as pioneer women labored collectively in their new frontier environment, they repeatedly eked out of their scarcity something to benefit those in need—Indian women and children, Saints confronting poverty and sickness, and impoverished immigrants.

New Beginnings in the West

A hiatus of ten years and thirteen hundred miles separated the Female Relief Society of Nauvoo, Illinois, from the Relief Society established in Utah Territory in 1854. The last recorded meeting of the Nauvoo Relief Society took place in March 1844.3 Between February and September 1846, thousands of Latter-day Saints followed Brigham Young and the Quorum of the Twelve Apostles in a mass exodus from Nauvoo. Seeking a new and uncontested home in the Rocky Mountains, the Saints trekked across the Great Plains to the Great Basin, with the first company arriving in the Valley of the Great Salt Lake in July 1847. By that fall, more than two thousand Saints had gathered in their new mountain home. The 1850 census numbered their ranks at 11,380.4

As Latter-day Saint women journeyed westward, generally in family groups—some of which were extended by plural marriage—they clustered informally to pray, sing, testify, prophesy, and bless, and they continued such gatherings in their new home. Shared privations forged close connections that facilitated women’s nursing of the sick and aid to the poor. But the formal reorganization of women as a cooperative component of church government according to the pattern established by the Female Relief Society of Nauvoo was not accomplished for several years. In Illinois in 1845, in the wake of the murders of Joseph and Hyrum Smith, Brigham Young had halted operations of the Female Relief Society, declaring he would “get up Relief Society” again when he decided to “summon them [the women] to my aid.”5 When Young called for the reestablishment of the Relief Society in the 1850s, he did so in a very different context than that which had given rise to the Female Relief Society of Nauvoo.

The remote mountain desert environment of the Great Basin posed new challenges for the Saints, not the least of which was association with the native peoples who had long occupied the area. In addition, a new and persistently conflicted connection between the church and the U.S. government began with the establishment of Utah Territory in 1850; that conflict intensified in subsequent years. Finally, as church leaders encouraged the immigration of thousands of converts from throughout the United States, Great Britain, and Europe, population in the Great Basin increased and Mormon colonization expanded to scattered areas of the territory, necessitating a more elaborate order of church governance and aid to those impoverished by immigration and resettlement. These realities shaped the form of Latter-day Saint women’s first Relief Societies in the West.

Female Council of Health and “Indian Relief Societies”

The hardships of the westward trek and isolated frontier settlement brought health concerns, including distinctly female concerns, to the forefront. Midwives and other women began attending meetings of the Council of Health with male practitioners when the group was formed in 1849.6 Some women, however, were uncomfortable discussing medical matters in the Council of Health, which caused “a slackness of attendence of the females, which was suposed to be caused by there being present male members.” As a result, the Female Council of Health was organized by July 1851.7 Midwife Phoebe Angell, mother of Brigham Young’s wife Mary Ann Angell, was designated president of the women’s council, and she chose two midwives as counselors. The women’s council met about twice a month, initially in Angell’s home. As membership expanded, the group later held some meetings in the newly erected tabernacle on the south end of the temple block.8 On November 13, 1852, the council selected one woman each from most of the city’s nineteen wards “to look after the poor.”9 After Angell died in November 1854, her counselor Martha “Patty” Sessions became president of the Female Council of Health, though by then Sessions was also serving as president of the newly organized Relief Society of Salt Lake City’s Sixteenth Ward.10

Beginning in the fall of 1853, Brigham Young and other church leaders sought to improve the Saints’ relations with American Indians, who resented a steadily increasing Mormon presence in the lands they inhabited. The close of 1853 had seen the waning of the Walker War, a series of bloody skirmishes between Utes (headed by Chief Wakara, known to Latter-day Saints as Walker) and settlers. Hoping to heal the fractured relationship, at the October 1853 general conference Young announced the assignment of two dozen missionaries to labor among local Indians; their task would be “to civilize them, teach them to work, and improve their condition by your utmost faith and diligence.”11 The effort to “civilize” the American Indians included instruction about agriculture and the adoption of Latter-day Saint religious beliefs and cultural practices, including in relationship to clothing. At the same conference, Parley P. Pratt of the Quorum of the Twelve spoke of redeeming “the children of Nephi and Laman,” Book of Mormon figures from whom, Saints believed, the American Indians descended. Further, Pratt called for assistance in clothing Indian women and children.12

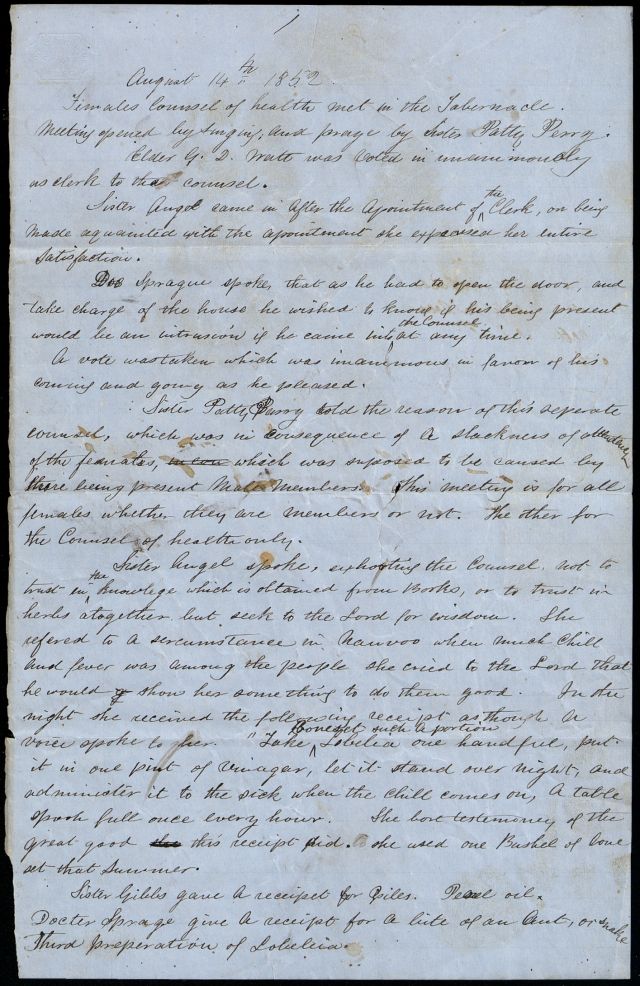

Female Council of Health minutes. This women’s organization in early Utah was a precursor of the Relief Societies that were formally reinstated in 1854. This minute entry for August 14, 1852, demonstrates women’s collaboration in addressing community needs through visits. (Church History Library, Salt Lake City.)

A group of seventeen women in Salt Lake City responded to Pratt’s call in February 1854 when they independently organized a “Socity of females for the purpose of making clothing for Indian women and Children” (see Document 2.1). They met weekly in various homes through the spring. In May, Young and other church leaders negotiated peace with Wakara and other chiefs in central Utah. Shortly thereafter, Young, in company with Pratt and other church leaders and their wives, toured the southern settlements and preached rapprochement with the Indians. When the company reached Harmony, Washington County, one of the newly arrived missionaries wrote, at Pratt’s suggestion, to the Deseret News: “We are much in want of old clothing, especially shirts, to help cover the nakedness of the Indians, especially of the women. What will the Salt Lake Saints do about it?”13

On June 4, 1854, less than a week after his return to the Salt Lake Valley, Young officially proposed to “the Sisters … to form themselves into societys to relieve the poor b[reth]ren” and “to clothe the Lamanite children and women and cover their nakedness.” He advised women to “meet in their own wards and it will do them good.”14 The response was immediate. On June 6, women in the Fourteenth Ward met with their bishop “to be organised into a society.”15 On June 10 Patty Sessions recorded that in the Sixteenth Ward “the sisters organised a benevolent society to clothe the Indians & squa[w]s I was put in Presidentes.”16 On June 13 the independent group of seventeen women disbanded and “each member joined the scociety in their own wards,” their president Matilda Dudley becoming president of the Thirteenth Ward Female Indian Relief Society (see Document 2.1). Brigham Young’s financial records list women’s contributions by ward, often under the designation “Indian Relief Society.” Societies in at least seventeen wards in the Salt Lake Valley donated clothing and bedding at a total value of $1,540, along with $44 in cash, to the church’s Indian relief effort in 1854 and 1855.17

Relief Society Expansion

As the urgent call for Indian relief subsided, some ward Relief Societies stopped meeting or were reconstituted to meet other needs. The Fourteenth Ward Female Relief Society, for example, was organized a second time “by Bishop [Abraham] Hoagland (agreeable to the request of President Brigham Young) on the seventeenth day of September 1856,” and Phebe Carter Woodruff was appointed president (see Document 2.3). She had been a member of the Female Relief Society of Nauvoo. Indeed, scattered through these early Relief Societies were women who had been associated with the Nauvoo Relief Society.18 Though many of the Saints in Utah had not been acquainted with the Nauvoo Relief Society, the simple organizational pattern inaugurated in Nauvoo was replicated within each ward: a president and two counselors, set apart by priesthood leaders, and committees to visit the ward by block to assess needs and collect donations for aiding the poor. Woodruff immediately established such committees in the Fourteenth Ward. There, as in other wards, meetings began with singing and prayer, followed sometimes by an address by a bishop or encouragement from the president or her counselors. Women gathered primarily to work together, often for a full day at a time. They might card or spin wool or sew quilts. Typically, they sewed carpet rags: stitching scraps of fabric together into long strips that could be rolled into manageable balls and then braided or woven on a loom to make carpet for the floors of a meetinghouse or home.

The Relief Societies helped fund immigration through the Perpetual Emigrating Fund, a system under which immigrants borrowed the costs of their travel to Utah and agreed to eventually repay the loans so that other converts could similarly benefit. In addition, Relief Society women also assisted arriving immigrants, including those who began to arrive in 1856 with the use of low-cost handcarts pulled by converts who walked across the plains. Lucy Meserve Smith, president of a Relief Society in Provo, forty miles south of Salt Lake City, recalled how in 1856 she and her associates gathered bedding and clothing for members of the Martin and Willie handcart companies stranded by early snows in the mountains of present-day Wyoming (see Document 2.4).

As Smith’s Provo group demonstrates, Female Relief Societies spread to Latter-day Saint settlements beyond the Salt Lake Valley. To the north, Relief Societies were organized in Bountiful, Ogden, and Willard. To the south, at least two Provo wards formed Relief Societies, as did wards farther south in Spanish Fork, Ephraim, and Manti. Cedar City, in Iron County, 250 miles south of Salt Lake City, established a Female Benevolent Society on November 20, 1856 (see Document 2.6). Documentation exists for some twenty-five ward Relief Societies in the 1850s, though there were almost certainly more.19 Producing an exact tally is difficult because sometimes women from several wards in an area met together as a single Relief Society, and sometimes a single ward formed multiple districts, with a president and counselors heading each district.

When Brigham Young called in June 1854 for the organization of Relief Societies, he advised they be formed within local wards, and he anticipated they would operate under the direction of the ward bishop who presided over the local congregation. Joseph Smith had maintained a close relationship with the Female Relief Society of Nauvoo, at least during its first year when he gave lengthy addresses at six of its meetings.20 The involvement of male priesthood leaders varied from ward to ward in the 1850s. In Cedar City, priesthood leaders often addressed the women’s meetings.21 In the Salt Lake City Seventh Ward, a new bishopric sought in March 1857 to “resurrect” a defunct Relief Society and then assigned the group such tasks as operating “directly to the assistance of the Bishop” in caring for the poor, providing assistance for converts arriving with “the Great Emigration,” and making a cushion for “the seat in the Stand.”22 Women in Willard, in northern Utah, initiated ad hoc committees to assist immigrants. Later they asked the bishop to formally organize them because “the need of a Relief Society was felt by the sisters who had belonged to the one organized by the Prophet Joseph Smith in Nauvoo.”23 In the Salt Lake City Fourteenth Ward, women independently drafted organizational bylaws and designated officers and committees beyond the traditional presidency and visiting committees (see Document 2.3).

The relationship between Relief Society leaders and priesthood leaders had become a question in Nauvoo, though following the death of Joseph Smith it was quickly overshadowed by the larger question of who had authority to preside as his successor, a question that deeply divided the church.24 The largest segment of members followed Brigham Young and the Quorum of the Twelve Apostles in the move westward, seeking in the isolation of the Great Basin to establish on a firmer footing the church and kingdom of God that Smith had envisioned. Through the 1850s church leaders moved beyond the exigencies of survival to establish civil and religious authority. Brigham Young and the First Presidency in Salt Lake City provided central direction as settlements spread north and south; members of the Quorum of the Twelve often presided in new areas. For example, George A. Smith, husband of Lucy Meserve Smith, presided over villages first in Iron County and then in Utah County (see Document 2.4). Generally, villages became wards, headed by bishops who worked under presiding authorities such as George A. Smith. Church leaders usually directed both civic and church affairs.

Though women were not part of the ecclesiastical priesthood structure of the church, the establishment of Relief Societies provided them a new collective presence in community-building during a period when cooperative labor was imperative. The name church leaders chose for their newly settled land—Deseret, interpreted in the Book of Mormon as “a honey bee”25— signaled the people’s commitment to and the necessity of communal industry. Some resources in the territory, including water and public lands, were managed under intertwined ecclesiastical and civil direction. Mormon men donated a portion of their time to public works projects such as constructing canals, fences, and the temple. Women gave of their time and means to aid in such projects as providing carpet for buildings used for both religious and civil purposes. The women’s organization worked largely independently, but not without the direction and approval of local priesthood leaders. The lack of total autonomy in this hierarchical system occasionally chafed women as well as men, and dissent was not unknown. Yet committed Latter-day Saints viewed unity and harmony as requirements for a latter-day Zion and felt keenly the imperative to become a people “of one heart and one mind.”26

Temples, such as those Saints had constructed earlier in Ohio and Illinois, played an essential role in the Saints’ experience. Though the first temple in the West was not completed until 1877, as early as 1851 church leaders set apart men and women to administer the rituals of the temple in other consecrated spaces.27 Families that had been established through temple marriage sealings, many of them polygamous families, were another manifestation of priesthood order. Church leaders taught that husbands and fathers presided in the family and that women, through temple ordinances, received priesthood keys “in connection with their husbands.”28 Church leaders’ sermons during this period emphasized the importance of the hierarchical priesthood order, as manifest in both ecclesiastical offices and the family.

In 1855 Joseph Smith’s addresses to the Nauvoo Relief Society appeared as part of the “History of Joseph Smith” series in the church’s Salt Lake City newspaper, the Deseret News (see Document 2.2). The printed versions of these discourses included changes approved by Brigham Young, church historian George A. Smith, and other leaders that, among other things, emphasized priesthood authority and order. There is no evidence that the publication changed the actual operation of local Relief Societies; they were already working under the direction of bishops. Perhaps the 1854 reestablishment of the Relief Society in the local units raised some of the same concerns that had surfaced in Nauvoo about the relationship between women of the Relief Society and the ecclesiastical priesthood structure governing the church.29

Principles of order and obedience received particular emphasis in 1856 and 1857 in a period that became known as the “Reformation.” Concerned about spiritual complacency, church leaders preached sermons throughout the territory, calling on Latter-day Saints to recommit to the faith.30 Lucy Meserve Smith explained, “The saints were called upon to confess our sins, renew our covenants, and all must be rebaptized for a remission of our sins, and strive to live more perfectly than ever before” (Document 2.4). The movement is particularly evident in minutes of the Cedar City Relief Society (see Document 2.6), where male and female leaders repeatedly emphasized obedience and orthodoxy. A member of the stake presidency exhorted Relief Society women in December 1856: “Let us stir ourselves and see if we cannot make a reformation in our houses, right in Cedar City,”31 a theme that women echoed as they visited women individually in their homes.

Impact of the Utah War

The Utah War, the 1857–1858 threat of armed conflict between Latter-day Saints and the U.S. government, enraged and terrified the residents of Utah and significantly disrupted ward Relief Society operations. In 1847, when Latter-day Saints first settled in the Salt Lake Valley, they had moved into Mexican territory. Then, at the close of the Mexican-American War in 1848, Mexico ceded its northern territories to the United States, including the Great Basin lands where the Saints had settled. Congress organized Utah Territory in 1850, and federal appointees began to play a major role in territorial governance. President Millard Fillmore balanced the selection of non-Mormon officials with Latter-day Saints, including Brigham Young as the first governor. The outside officials generally distrusted the Saints’ beliefs and practices, particularly plural marriage and the meshing of religious and civil authority. Mounting misunderstandings culminated in 1857 when President James Buchanan sent a large contingent of federal troops to Utah to quash a rumored “Mormon rebellion” and install a new governor to replace Young. Fearing the same violence the Saints had experienced in Missouri and Illinois, Young declared martial law and stationed militias in the mountains to prevent the entry of U.S. troops into the valleys the Saints had settled. In the fall of 1857, Relief Society women knitted woolen stockings, mittens, and other winter clothing for the Saints’ army.

The following spring, Young directed residents in the Salt Lake Valley and other northern settlements to evacuate their homes and prepare private and public buildings for burning in the event the troops should enter the valley. Thousands of Saints migrated southward, many of them insufficiently prepared for the trek. Records kept by the Salt Lake City Seventh Ward Relief Society noted that members provided “to a woman from the North as she was moving South One pair of shoes some linsey for her children & a pease of carpet for a bedspread.”32 Emmeline B. Wells wrote that “the regularity of the [Relief Society] work was interrupted in 1858 by the entire people moving south. … All the money then on hand was expended for food and clothing for the poor.”33 In 1858 Patience Palmer was the Relief Society president in Ogden, forty miles north of Salt Lake City. Her son later recalled that his mother’s “Relief Society distributed the carpet the rag carpet for wagon covers, and the woolen carpet for skirts for the women and shirts for men and children. … One could see trains of families by the hundreds leaving their homes, their gardens, their fields and everything.” The Palmers went to Spanish Fork, where they lived “all summer in a willow shack.”34

By July 1858 displaced Latter-day Saints had begun returning to their homes after a compromise was reached between Latter-day Saint leaders and the new Utah governor, and the federal troops had established Camp Floyd forty-five miles southwest of Salt Lake City.35 The “move south,” however, had profoundly disrupted their lives and their local congregations. Edwin D. Woolley, bishop of Salt Lake City’s Thirteenth Ward, complained that, following church members’ return, it was “impossible to get up meetings.” The Relief Society had already disbanded, and the ward only rarely met for Sunday worship meetings over the next year.36

Nearly all Relief Societies, whether those in wards that moved south or in wards that received evacuees, seemed to vanish after 1858, not to reappear for a decade. There were exceptions such as in Spanish Fork, where Priscilla Merriman Evans left a record of Relief Society operations continuing until and beyond 1867 (Document 2.5). Brigham Young called again for the reestablishment of Relief Societies churchwide in 1867.37 Having experienced two substantial interruptions in Relief Society operations—from 1844 to 1854 and from 1858 to 1867—women now would find ways to make it a permanent part of church structure.

Cite this page

Footnotes

Footnotes

-

[1]“Relief Society,” in East Bountiful Ward, Davis Stake, Manuscript History and Historical Reports, 1877–1897, CHL.

-

[2]A history of this Relief Society indicated that it “was discontinued November 1857” after “just a little more than 6 months duration” because of the tumult in Utah Territory caused by the Utah War. (“History of the Bountiful First Ward Relief Society Beginning 24 April 1857 to 5 February 1961” [unpublished typescript, 1961], copy at CHL, 1.)

-

[3]See Document 1.2, entry for Mar. 16, 1844.

-

[4]James B. Allen and Glen M. Leonard, The Story of the Latter-day Saints (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 1976), 220–225, 234–238, 241–247.

-

[5]Document 1.13.

-

[6]Priddy Meeks, Reminiscences, 1879, typescript, CHL, 60–62; Historical Department, Journal History of the Church, 1896–, CHL, Jan. 21 and Mar. 21, 1849; Patty Bartlett Sessions, Diary, May 8, 1850, in Donna Toland Smart, ed., Mormon Midwife: The 1846–1888 Diaries of Patty Bartlett Sessions, Life Writings of Frontier Women 2 (Logan: Utah State University Press, 1997), 146.

-

[7]Female Council of Health, Minutes, Aug. 14, 1852, CHL; Sessions, Diary, July 8, 1851, in Smart, Mormon Midwife, 166.

-

[8]Sessions, Diary, Sept. 17, 1851; Mar. 24 and May 12, 1852, in Smart, Mormon Midwife, 168, 174, 176; Female Council of Health, Minutes, Aug. 14, 1852, CHL; Richard L. Jensen, “Forgotten Relief Societies, 1844–67,” Dialogue: A Journal of Mormon Thought 16, no. 1 (Spring 1983): 107.

-

[9]Sessions, Diary, Nov. 13, 1852, in Smart, Mormon Midwife, 182.

-

[10]Sessions, Diary, June 10 and Nov. 16, 1854, in Smart, Mormon Midwife, 205, 210.

-

[11]Brigham Young, Discourse, Oct. 9, 1854, in Deseret News, Nov. 24, 1853, [2]; see also Brigham Young, Heber C. Kimball, and Willard Richards, “Tenth General Epistle,” Deseret News, Oct. 15, 1853, [3].

-

[12]Parley P. Pratt, Remarks, Oct. 9, 1853, in “Minutes of the General Conference,” Deseret News, Oct. 15, 1853, [3].

-

[13]T. D. Brown, May 19, 1854, Letter to the Editor, Deseret News, June 22, 1854, [2].

-

[14]Brigham Young, Remarks, June 4, 1854, in Historian’s Office, General Church Minutes, 1839–1877, CHL; Edyth Jenkins Romney, Thomas Bullock Minutes (Loose Papers), 1848–1856, Brigham Young Office Files Transcriptions, 1974–1978, CHL.

-

[15]Eliza Maria Partridge Lyman, Journal, 1846–1885, CHL, June 6, 1854.

-

[16]Sessions, Diary, June 10, 1854, in Smart, Mormon Midwife, 205.

-

[17]Financial Journal, July 1853–Nov. 1854, Brigham Young Office Files, 1832–1878, CHL; Jensen, “Forgotten Relief Societies,” 114–115.

-

[18]Many other women appointed as ward Relief Society presidents in the 1850s had been members of the Female Relief Society of Nauvoo, including, in Salt Lake City, Lydia Goldthwaite Knight (First Ward), Amanda Barnes Smith (Twelfth Ward), Lydia Granger (Fifteenth Ward), Sarah Granger Kimball (Fifteenth Ward), and Patty Sessions (Sixteenth Ward); in Bountiful, Elizabeth Haven Barlow; in Ogden, Patience Delila Pierce Palmer; in Willard, Mary Ann Hubbard; and in Spanish Fork, Lucretia Gay.

-

[19]Jill Mulvay Derr, “The Relief Society, 1854–1881,” in Mapping Mormonism: An Atlas of Latter-day Saint History, ed. Brandon S. Plewe (Provo, UT: Brigham Young University Press, 2012), 102; Jensen, “Forgotten Relief Societies,” 113, 119; “History of the Bountiful First Ward Relief Society,” 1.

-

[20]See Document 1.2, entries for Mar. 17, Mar. 31, Apr. 28, May 26, June 9, and Aug. 31, 1842.

-

[21]See Cedar City Ward, Parowan Stake, Cedar City Ward Relief Society Minute Book, 1856–1875, CHL.

-

[22]Seventh Ward Relief Society, Minutes, Mar. 24, 1857, Seventh Ward, Salt Lake Stake, Relief Society Records, 1858–1875, CHL.

-

[23]Relief Society History, not before 1915, p. 1, inserted in Relief Society Minutes and Records, vol. 14, Brigham City First Ward, Box Elder Stake, Brigham City First Ward Relief Society Minutes and Records, 1878–1982, CHL.

-

[24]See introduction to Document 1.13.

-

[27]The temple rituals were performed in the Council House beginning in 1851 and in the Endowment House following its May 1855 dedication. (See Lisle G. Brown, “‘Temple pro Tempore’: The Salt Lake City Endowment House,” Journal of Mormon History 34, no. 4 [Fall 2008]: 4–8.)

-

[28]See revised version of Joseph Smith’s April 28, 1842, address to the Relief Society, in Document 2.2.

-

[29]See Document 1.2, entry for Mar. 16, 1844; Document 1.13; and introduction to Part 1.

-

[30]Paul H. Peterson, “The Mormon Reformation of 1856–1857: The Rhetoric and the Reality,” Journal of Mormon History 15 (1989): 59–87.

-

[31]Cedar City Ward, Parowan Stake, Cedar City Ward Relief Society Minute Book, Dec. 3, 1856.

-

[32]Seventh Ward Relief Society, bk. A, Sept. 24, 1858, p. 31, Seventh Ward, Pioneer Stake, Relief Society Minutes and Records, 1848–1922, CHL.

-

[33]Emmeline B. Wells, ed., Charities and Philanthropies: Woman’s Work in Utah (Salt Lake City: George Q. Cannon and Sons, 1893), 12.

-

[34]William Moroni Palmer, “A Sketch of the Life of Patience Delila Pierce Palmer,” ca. 1927, CHL.

-

[35]On the Utah War, see William P. MacKinnon, ed., At Sword’s Point, Part 1: A Documentary History of the Utah War to 1858, Kingdom in the West, the Mormons and the American Frontier 10 (Norman, OK: Arthur H. Clark, 2008); and Matthew J. Grow, “Liberty to the Downtrodden”: Thomas L. Kane, Romantic Reformer (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2009), 149–206.

-

[36]Ronald W. Walker, “‘Going to Meeting’ in Salt Lake City’s Thirteenth Ward, 1849–1881: A Microanalysis,” in New Views of Mormon History: A Collection of Essays in Honor of Leonard J. Arrington, ed. Davis Bitton and Maureen Ursenbach Beecher (Salt Lake City: University of Utah Press, 1987), 147.

-

[37]See Document 3.1.